Robert Frost: Poet of Man and Nature

For Frost, nature is nature touched by human perception, not as such

It must have been the name. Before I ever read “Dust of Snow” or “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” I thought of Robert Frost as a poet of winter. Before I ever cracked its spine, the mint green cover of his selected poems evoked the month of January.

My intuition was a good one. Frost is a great American nature poet, arguably the greatest. His intimate knowledge of the flora, fauna, and winters of New England renders that landscape universal. His nature poetry is not merely raptures over greenery. Poems like “Birches” and “Mowing” emerge from a specific context, yet they allow readers to discover in that specificity a shareable moment of insight.

Admirers of Frost, however, know that he was more than a nature poet. A master of the dramatic monologue unlike any since Robert Browning, Frost is also a storyteller. Using the same blank verse dialogue Shakespeare did in his plays, he tells stories of the rural uncanny. These poems features witches, widows, unreliable guides, and spouses caught at moments of revelation. In them, Frost proves as sharp an observer of human nature as of the natural world.

It wasn’t until I read New Hampshire, the collection that earned Frost his first Pulitzer Prize and launched him into literary stardom, that I fully comprehended how these two parts of the poet—the naturalist and the humanist—fit together. As it turns out, Frost never attempted in his mature poetry to portray nature as such, but only nature as it is touched—and altered—by human experience.

The title poem of New Hampshire attests to this twin focus. “New Hampshire” is a long monologue by a Frost-like speaker, confessing his deep love for the state. What strikes this man about New Hampshire is its lack of commerce. Every other state has its special industry or product, while every resident of the rest of the (then) 48 states is busy buying and selling, hawking and huckstering. New Hampshire has only “specimens”—“One each of everything as in a showcase, / Which naturally she doesn't care to sell.” He goes on:

One each of everything as in a showcase.

More than enough land for a specimen

You'll say she has, but there there enters in

Something else to protect her from herself.

There quality makes up for quantity.

Not even New Hampshire farms are much for sale.

..................................................

Apples? New Hampshire has them, but unsprayed,

With no suspicion in stern end or blossom end

Of vitriol or arsenate of lead,

And so not good for anything but cider.New Hampshire is a refuge from the state of constant busyness, not to mention business, that pervades the nation.

It is also and perhaps for the same reason distinguished by its natural beauty and its fascinating human “specimens.” The rest of New Hampshire, in fact, unfolds as a series of “notes” on this initial poem, treating first the people, then the nature that compose the state. Many of these poems are justly famous. They include “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” mentioned above, but also “Fire and Ice,” “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” “The Witch of Coös,” and “The Need of Being Versed in Country Things”—a veritable hit parade of beloved Frost poems.

But it was another set of lines in “New Hampshire” that brought home to me the signal importance for Frost of the nature-man entanglement.

Near the end of this rather free-wheeling poem, the speaker takes up the topic of nature worship. Distancing himself from the Transcendentalist tradition to which you might expect a New England nature poet to adhere, Frost’s stand-in is wary of the sublime. The horror of nature worship that recurs throughout the Hebrew Bible lets him express why:

Even to say the groves were God’s first temples

Comes too near to Ahaz’ sin for safety.

Nothing not built with hands of course is sacred.In the next line, he assures us that “here is not a question of what’s sacred; / Rather of what to face or run away from,” but the insight—the fiercely anti-pagan insight that the sacred comes from nature mixed with human effort—resonates throughout the collection.

To face up to modernity, the huckstering mentality that besieges American life, you can’t just retreat to the mountains of New Hampshire. You must bring something back. Nature unmixed with human effort is no refuge but a terror at least equal to the onslaught of modernity. What Frost brings back is poetry.

This line of thought explains the seemingly boundless arrogance of “The Aim Was Song.” The conceit of the poem is that human beings taught the wind how to blow. That is, how to blow “right.” It reads, in full:

Before man came to blow it right

The wind once blew itself untaught,

And did its loudest day and night

In any rough place where it caught.

Man came to tell it what was wrong:

It hadn’t found the place to blow;

It blew too hard—the aim was song.

And listen—how it ought to go!

He took a little in his mouth,

And held it long enough for north

To be converted into south,

And then by measure blew it forth.

By measure. It was word and note,

The wind the wind had meant to be—

A little through the lips and throat.

The aim was song—the wind could see.Human beings add something to the natural world. This is how we can dare to teach the wind to blow. While there is a tongue-in-cheek quality to the poem, it is due to the absurdity of the situation, not the fact of it. To be sure, the natural world is self-sufficient. It overawes us. And yet we puny creatures have something—the ability to create art, to make out of the beauty of existence something lasting—that all the rest of nature combined can’t muster. It’s funny, but it’s true.

No, Frost isn’t interested in nature as such. Its magnitude too much outstrips us. He is interested in what people learn about themselves by being in nature, by going outside and looking back on themselves from without. It is what we carry back for our dialogues, our odd encounters with one another, which moves him. Hence the two parts of New Hampshire—the tales of human encounter and the epiphanies experienced in nature—brought together for a while in the garrulous title poem.

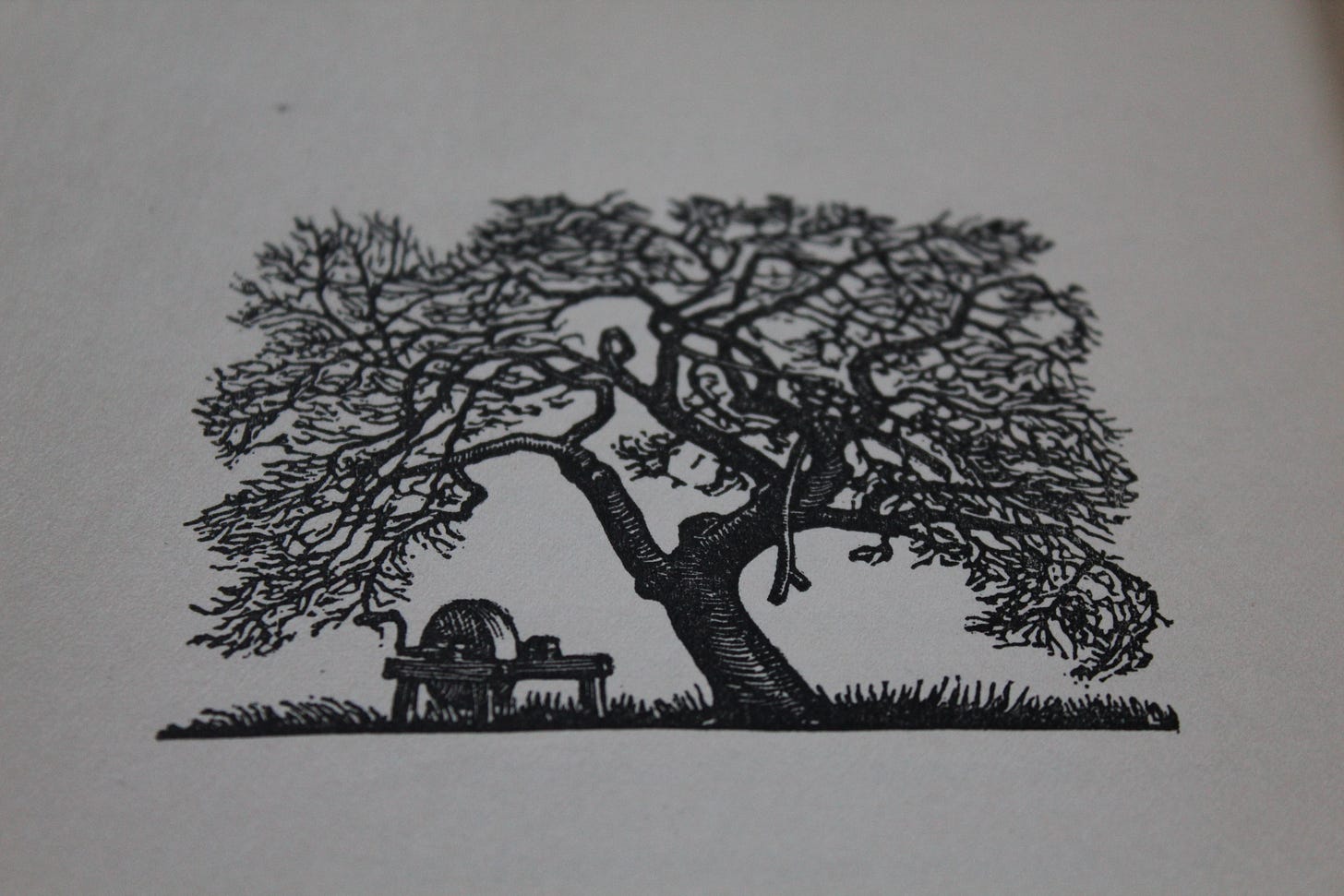

The first edition of New Hampshire is interspersed with woodcuts by the illustrator J.J. Lankes. The final woodcut perfectly captures Frost’s dual obsession. A large, hand cranked grinding stone stands beside a tree. The grinding stone look low and squat in comparison. But the product of that stone, a sharpened ax blade, can topple the tree. So the grinding stone and the tree stand together in unmatched symmetry.

While poetry is no doubt symbolized in the grinding stone, Frost knew that an ax blade without a handle—or with, heaven forbid. a rubber one—is a diminished tool. And without anything to chop, it is nothing at all. Both are necessary for the poet’s art.